Barrons: A Long List of Worries

Article by Reshma Kapadia in Barron's

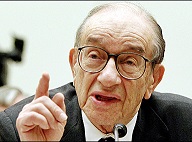

The U.S. economy may be in the middle of one of the longest recoveries ever, but Alan Greenspan tells Barron’s that the economy doesn’t look so great—and could well get worse.

The challenges that Greenspan sees are familiar ones, such as the ballooning deficit and the rising costs of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare. But the former Federal Reserve chairman says there’s an urgency in tackling these problems as inflation looms, populism spreads, and China’s economic might increases.

Now, a decade later, Greenspan has co-authored Capitalism in America with Adrian Wooldridge, an editor at the Economist. The new book traces U.S. economic history since colonial times to see what has helped the U.S. stand apart, and shed light on why its leadership is in jeopardy today.

Greenspan, now 92, presided over a period of economic prosperity from 1987 to 2006 that earned him rock-star-like devotion by investors, politicians, and even other central bankers; they hung on his often-inscrutable comments about the economy and monetary policy.

Greenspan, who is famous for his mastery of data, offers one statistic that sums up the problem today: productivity growth—or more specifically, the lack of it. Barron’s met with Greenspan in his Washington, D.C., office for a wide-ranging talk that covered the increasing threat from anemic productivity growth; the crisis that investors should be watching for.

Barron’s: Given the challenges to the U.S. economy you lay out in your book, is the Trump administration’s target of 3% economic growth sustainable?

Greenspan: Noooo!

Barron's: What is a more realistic growth rate?

Greenspan: Each $1 in entitlement spending crowds out $1 in savings. And gross domestic savings is what historically has gone to finance domestic investments such as infrastructure like roads and bridges, and private-sector capital spending on things like plants and equipment—hence, productivity growth.

Barron's: Has domestic savings declined or entitlement spending increased significantly?

Greenspan: Savings as a percentage of GDP has declined steadily since 1965. This had been mirrored by steadily rising entitlement spending over the same period. Neither are necessarily accelerating, but are becoming ever-larger drags on the fiscal budget and private investment. We used to have fairly substantial productivity growth, over 2% annualized. We are now at 1% for the most recent five-year period. Entitlements are slowing the rate of productivity growth. Entitlements are mandated, and their volume is largely unrelated to overall economic activity. Add that to our borrowing from everyone who will lend us a nickel, and it has put us into a serious straitjacket.

Barron's: In your book, you note that the number of Americans ages 65 and older will increase by 30 million, while working-age Americans will increase by only 14 million, creating a “fiscal challenge” bigger than any America has faced.

Greenspan: The 2018 report of the Old-Age & Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Trust Funds shows that despite the fact that everyone says we are funding this stuff, the actuaries are saying you have to cut benefits by 25% for to be sound. It’s such a big news item, they put it on page 296. It’s politically incorrect to talk about it. We’ve run out of money on many occasions the cost of benefits outstripped tax collection in the 1980s and again in 2010. Did we cut the benefit? No. We increased expenditures in some form or another and funded it out of general revenue, which contributes to a higher deficit and, by extension, a higher federal debt.

Clearly, entitlements are going to rise further as the population ages.

Barron's: Can anemic productivity growth spark a crisis?

Greenspan: [Nods yes]. What it causes is populism. As productivity slows down, GDP slows down and everyone is dissatisfied. It’s not just the U.S. that has a problem: About half of the major economies had annualized productivity growth of 1% or less over the past five years, as measured by output per employee. These are all fundamentally disastrous numbers.

Barron's: Populism has contributed to escalating trade tensions with China. How does a trade war affect the economy?

Greenspan: Tariffs are exactly the same as an excise tax. If you think you are going to raise the excise taxes in your country to beat the country over here—the people trying to ship into you—you are shooting yourself in the foot. President Trump would say that if China loses more than we do, that we won. Well, good luck. Tell that to your taxpayers. There are no winners in a trade war.

Barron's: As you look out across the landscape, where do you see crisis brewing?

Greenspan: Crisis gets generated after a period of time when you disregard something. Most recently, we’ve disregarded the federal budget. We are going to have a $1 trillion deficit in the next fiscal year, and there is no screaming and yelling. The reason? There’s this idea that the deficit doesn’t affect my pocketbook. You have to wait until the consequences of the deficit emerge.

Barron's: When do the consequences show up?

Greenspan: No politician gets out on the stump and says to constituents, “Our budget deficit is X trillion dollars.” One person in 100 knows what he is talking about. But when inflation goes up to 4%, to 5%, it is politically disastrous. That’s when it becomes an issue. But when it starts rising, it’s already too late in the game to stabilize it.

Barron's: What happens then?

Greenspan: We are working toward stagflation as characterized by a weaker economy and inflation. During the 1980s, we had an obvious occurrence of that. The Federal Reserve can put a clamp on it as [then Federal Reserve Chairman Paul] Volcker did. It lasted for two to three years, and it brought it to a halt. I don’t think it will be different this time.

Barron's: What’s the ramification of the end of QE?

Greenspan: Interest rates are going up.

Barron's: What does this all mean for the markets and bonds?

Greenspan: I’ve been saying for a while we have a bond market bubble—and we still have one. It’s the nature of a bubble that it continues to inflate with nothing happening. That’s the problem.

Barron's: Investors often look to bonds for safety. Should they no longer think that?

Greenspan: People believe there are people on Mars.

Barron's: Given the challenges facing the U.S. economy, what’s your recipe for making America’s economy great again?

Greenspan: Take a look at what Sweden did in the late 1990s. They were way ahead of us in terms of being behind the curve. And since it’s a socialist state, they were also [in worse shape] than us. They finally ran into a huge crisis; mortgage rates went to 500% for a short period, and the whole system was coming apart at the seams. A new government came in, and Sweden revamped its whole system from a defined-benefits program to a defined-contribution program. We need to change the structure of all the various social programs that have a trust fund to them and go to a defined contribution rather than defined benefit.

Barron's: Does our system need to come apart at the seams for action?

Greenspan: Of course! That’s what the danger is. You don’t see these crises arising until it’s at your doorstep.

To read this article in Barron's in its entirety, click here